Ultima Ratio Regum

By Mark Johnson (Twitter)

This year in the ongoing development of Ultima Ratio Regum, a ten-year experimental roguelike project focused on the procedural generation of culture and cultural behaviours, my focus has been almost entirely on people. The world has been notoriously devoid of human life for several years despite the tremendous social, religious and political detail that has gone into the worldbuilding, and it was finally time – with all these foundational elements in place – to change that.

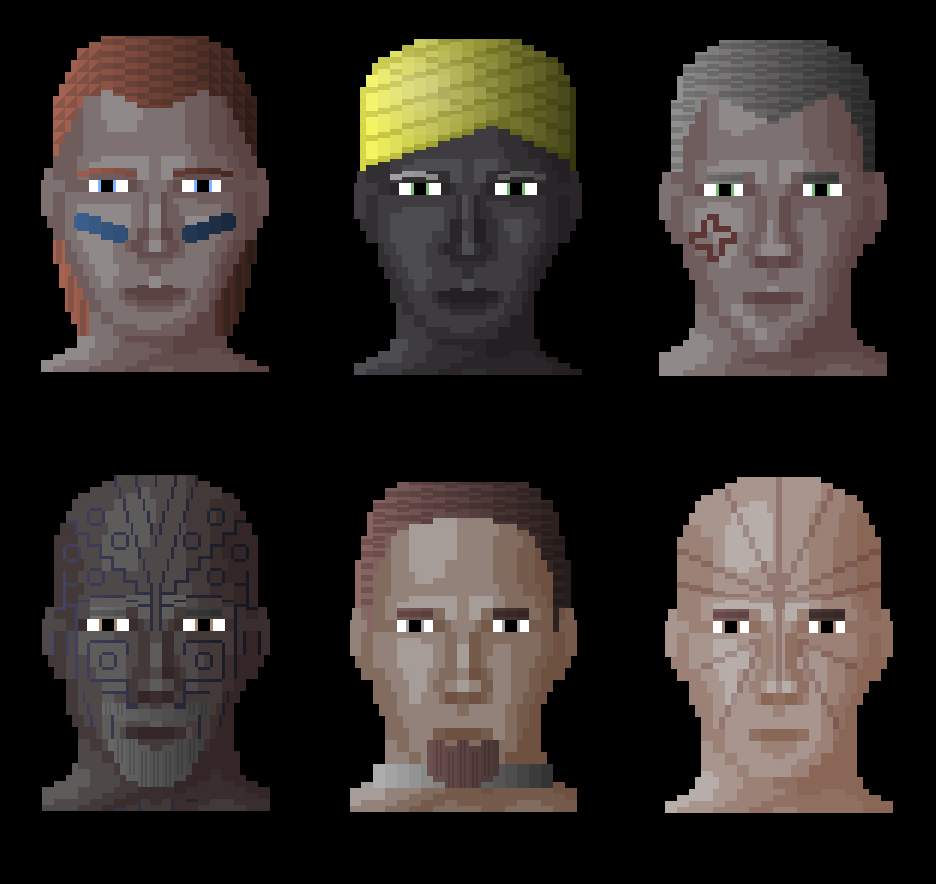

Firstly, what should they look like? I wound up creating an interwoven two part model of biological and cultural NPC elements. On the biological front, we have a range of variations: different genetic groups have different randomly-selected shapes of eyes, chins, necks, ears, noses, and so forth, alongside different colours for their hair, and their eyes. Skin tone of course varies with how close to the equator a particular person’s family originally hail from, with an appropriate range of variation from the darkest black to the palest white. I then combined these with cultural elements, which take two distinct forms: cultural elements that are applied to an NPC’s face (the only part of their “body” you can see in-game), and those applied to the items (clothing, weapons, etc) that a character happens to carry with them. On the faces of NPCs we find a massive range of hairstyles for both women and men which vary with culture, along with sets of distinctive cultural practices: scarification, tattooing, specific kinds of jewellery, turbans, paint markings, and many others.

This was then joined by clothing styles, for which I found myself building a rather detailed procedural clothing style generator. Clothing styles can have shirts and trousers, waistcoats and skirts, dresses, or togas, or anything in-between, with additional variation in style and appearance determined by the overall aesthetic preferences of the nation in question for certain shapes, certain colours, and so forth. Styles are distinctive either to entire cultures, or to niche demographics within a culture, such as the religious clergy, or soldiers. Each clothing style then breaks down into multiple tiers, helping the player identify the status of an unknown NPC and adding far greater variation to this part of the game visuals.

This therefore allowed for the interesting intersection of biological and cultural traits, and the ability for the player to play detective. Consider an empire from an equatorial region – the player is used to encountering characters with a dark skin-tone wearing a certain set of clothing and jewellery. At some point, however, the player happens to bump into a pale-skinned character with a different hair colour, who nevertheless possesses the same clothing styles (so biological difference, cultural similarity). Does this person represent a conquered colony? A trader trying to fit in? A slave or servant? Or something else? Nothing of this sort is ever explicitly told to the player, and so the player must instead rely on their knowledge of that particular generated world in order to draw conclusions based on their physical appearance, their clothes and any facial cultural traits, as well as their actions and patterns of speech, which brings us to our latter point – what NPCs actually do.

Developing NPC behaviours means how they spend their day, and how they talk to the player. The NPCs in URR now range from mercenaries to priests, guards to merchants, farmers to inquisitors, and arena fighters to servants and eunuchs. Each NPC class spawns and lives in a different part of the map and has a very different set of rules for their average everyday behaviours – take, for example, this screenshot of priests and worshipers (standard humans, shown with an “h”) going about their day.

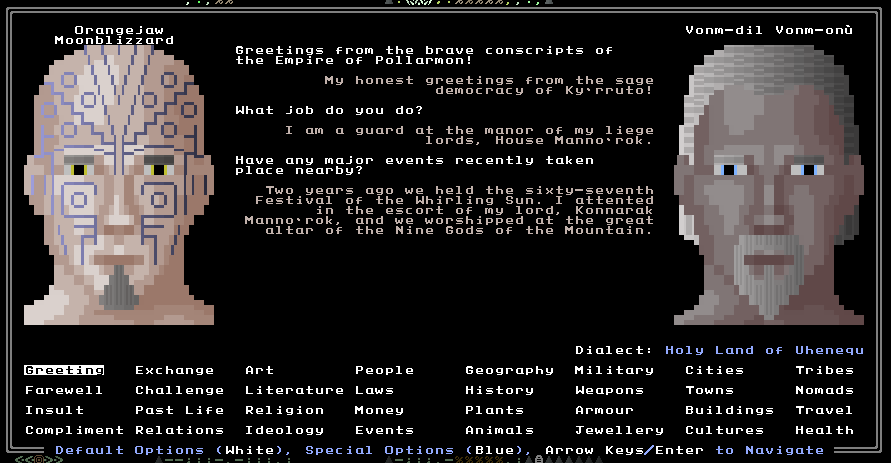

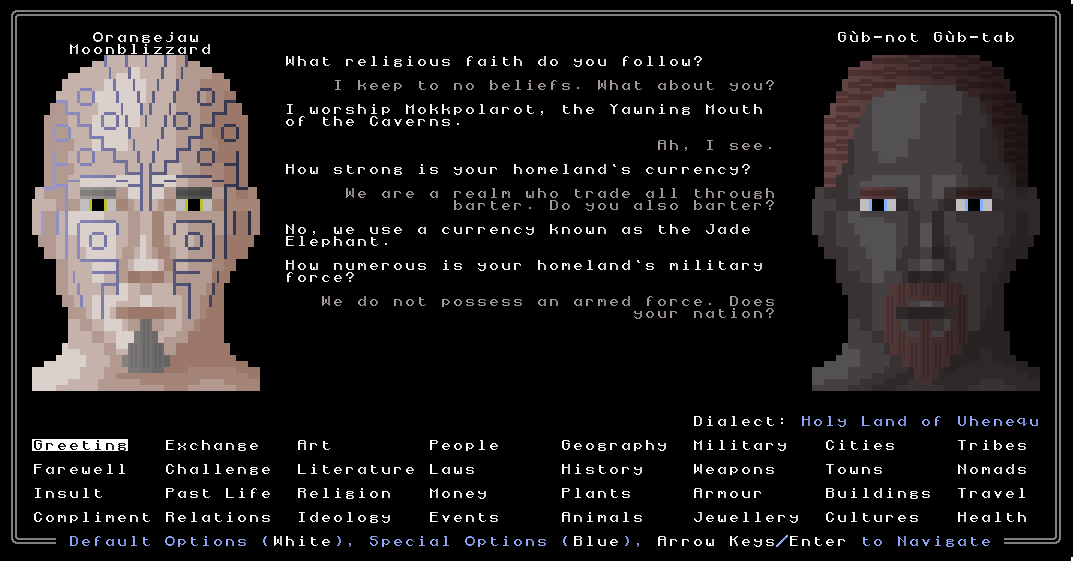

These highly active NPCs are then married with a pretty unusual speech system. Joining us now in this last part of 2016’s URR journey will be Orangejaw Moonblizzard, my profoundly procedurally-generated and facially-tattooed playtesting character who has travelled with me for over a month now – which is to say, I haven’t in this time needed to generate a new world to experiment with, and thereby expunge brave Orangejaw from existence. The goal was to create a speech system where the player could ask a tremendous range of questions without having to resort to programming it as a “chatbot”, to create realistic (or at least realistic-ish) human conversations, and to allow the player to uncover large volumes of information about the game world simply by speaking to its inhabitants. AS things stand now, I feel very confident this objective is almost complete: